Being off grid (without utility hookups to water, gas, and electricity) is challenging even just for a dwelling – but even more so for a farm, especially in this climate. In the spring, we have to start our plants indoors, so they will be developed enough to produce before it gets too hot for the cool weather plants in summer, and before the killing frosts of fall take out the heat lovers. They all need to be kept warm day and night, especially when germinating from seeds – but they also need to be under good bright sunlight. The sunlight is great in the greenhouse, which also gets plenty warm most days if it’s not totally cloudy – but greenhouses lose heat quickly after sundown. We solved for this in previous years by nightly driving all the baby plants up to the trailer, where they slept toastily on floor-to-ceiling shelving next to the wood stove.

Then every morning just after dawn, we drove them all back down to the greenhouse for their daily sunshine. We worked out a good two-person method to get it done as efficiently as possible, but it was a time-consuming process – and we couldn’t have the lights on near the plants when they were inside (or they’d get leggy trying to get fed by the artificial lighting). Yeah, it worked … but we needed to come up with something better.

Heating the greenhouse at night was the obvious solution, but it seemed impossible – the plastic covering lost heat so quickly that it would cost us a fortune in propane … and we’d always be fearful that the tank was going to run out in the night, leaving all our crops to freeze to death. And of course our little solar power system was not capable of generating enough electric heat (which is inherently inefficient) to do the job. A wood stove like the one we use in the trailer would require repeated fueling throughout the night, and again, the heat would mostly be going to the roof and then out through the plastic film.

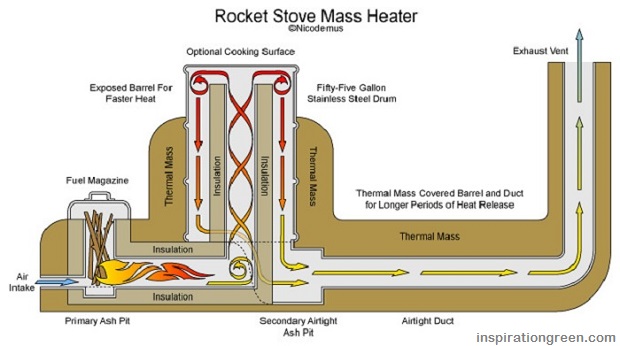

Research led us toward a possible solution – “rocket mass heaters,” which use small amounts of wood burned efficiently at high temperatures to heat up a thermal mass, which then slowly radiates the heat outward for many hours after the fire has gone out.

It would still be a challenge to heat the whole greenhouse with this method unless we built a prohibitively large heater, however. Hmmm.

Well, we’d already been experimenting with a technique that Elliot Coleman promotes, using row cover fabric to create a greenhouse-within-a-greenhouse – just putting the plants on the ground and covering them inside a low tunnel of fabric kept them warmer than the surrounding air, thanks to the day’s heat in the soil. That only got us a few degrees, but it was a crucial difference when temps might be just barely dipping below freezing.

What if we did the same thing atop a thermal mass? It seemed like a winning idea – so we decided to build a heated bench sized for seed trays, and put a cover over them at night to hold heat in.

For a year, we researched and gathered materials for the build – scavenged from garbage and the Free section of Craigslist; two trailer loads of clay from a retired sculptor, stove pipe of various diameters, a 55 gallon drum, river rocks from the neighbor’s pile they’d unearthed when building their house, cement board, and bricks – the best score of all was a huge free load of white “insulative firebricks,” which withstand high heat without heating up much themselves – ideal for our purposes.

Last fall, after the killing frost had come and the 2015 CSA was over, we got to work, starting to test combustion chamber designs the day after our CSA potluck.

There was a long period of trying out different brick layouts – the proportions of the combustion chamber are crucial to get right – for the rest of the fall, “CSA” ceased to mean “Community Supported Agriculture,” and became ‘Cross Sectional Area” – the entire system had to maintain the same CSA throughout the system, from fuel feed to exhaust, from rectangular tunnels to round pipes. I won’t bore you with all of the proportional rules that had to be followed, but know there was a lot of subtle and annoying math at this stage.

Many variations were tried out and discarded in the design process. The red bricks are used in the fuel feed for their durability, while the softer insulative bricks were used throughout the rest of the combustion system.

And then winter came, and we hit the road, leaving the wet clay of the combustion chamber to slowly dry out over the wintertime.

When we returned in March, we got to work on the thermal mass bench … which turned out to be a lot more work than we’d bargained for.

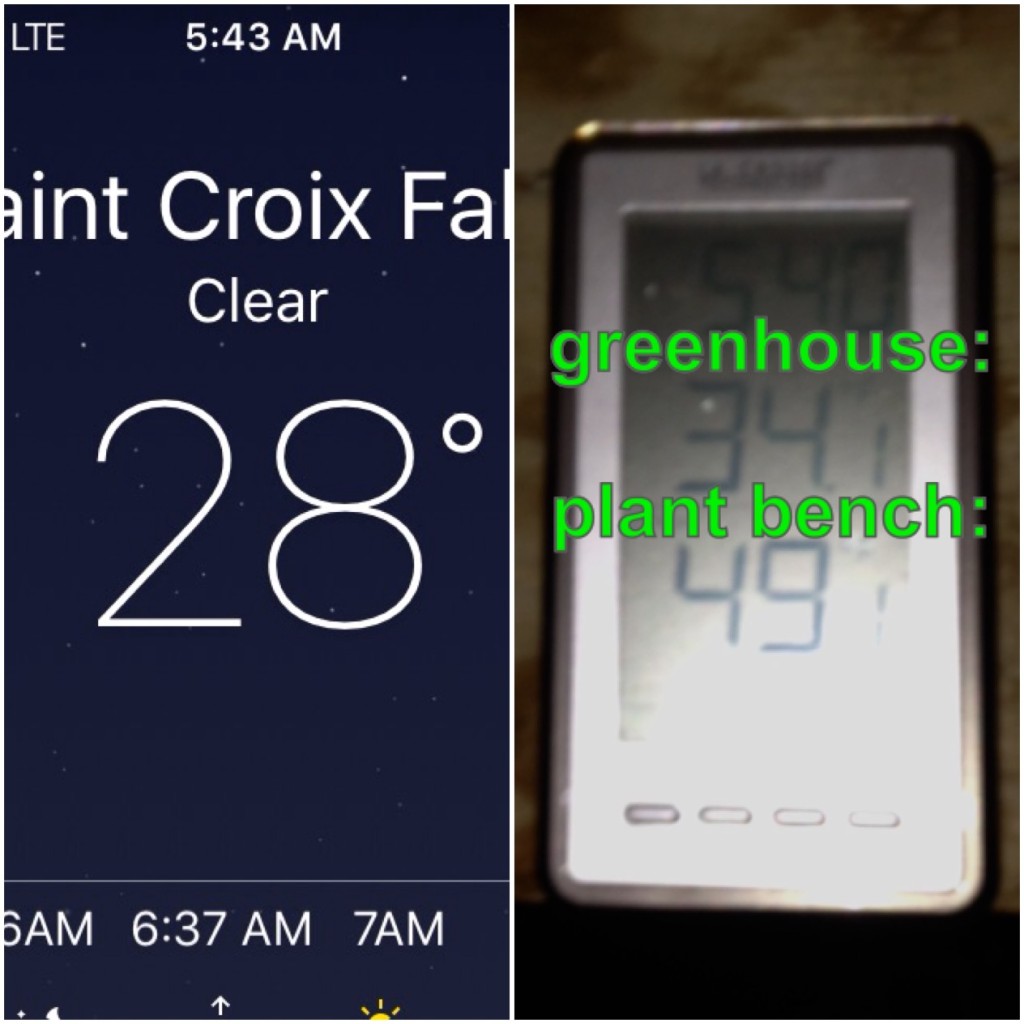

Before the chimney was upgraded further and before the thermal mass was fully dry – it was already working! Temperatures on the plant try bench stayed over 20 degrees warmer than outside, night after night – with no need to tend the fire after bedtime, and zero risk of the heat going out in the night – you can’t stop a warm giant rock from radiating! Plus it was warming the soil itself, and not just the air around the plants – great for happy, healthy root development.

It’s been a success. In recent nights just below 40 degrees, it kept the hot weather plants happily over 60 all night – maintaining the same 20+ degree heat increase seen at lower temps. It feels great to have it finally done, and really working wonderfully for our needs. It was a lot of work, but it was absolutely worth it. Plus, now we have experience in mass heater construction, so a mass heater in a future home is definitely a possibility …